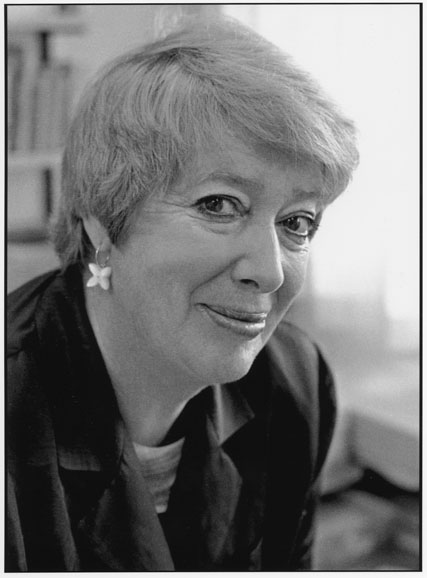

Photo by Reg Graham

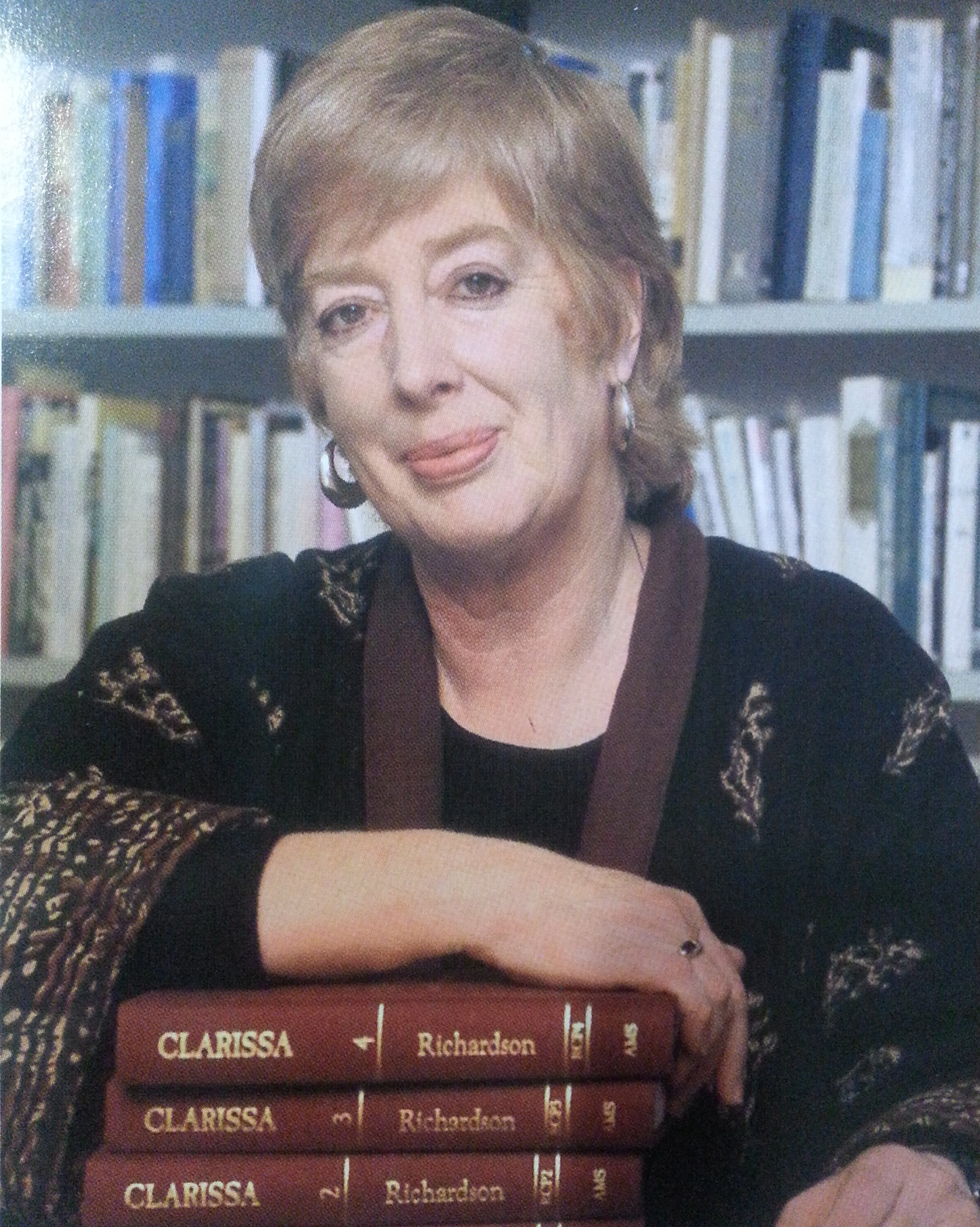

- I always try to catch Jane Austen in the act of creation by finding out what she read, what she saw, and what she made of it all. My quest began when I edited her favorite book in the world, Samuel Richardson’s History of Sir Charles Grandison. I read it until I knew it almost as well as she did. As I was writing Jane Austen’s Art of Memory, I often found her plucking scenes, characters, and even phrases from Grandison, playing with them, expanding on them, sometimes laughing at them, but always making of them something new and all her own.

Many critics take at face value Austen’s self-deprecating remark to the Prince Regent’s chaplain that she was “the most unlearned, & uninformed Female who ever dare to be an Authoress,” but I believe that her tenacious memory enabled her to create those brilliant novels. Austen engages in friendly dialogue as well as rivalry with earlier writers, who included Shakespeare, Milton, Richardson, Locke, and — unexpectedly — Chaucer. I also suggest new theories about Austen’s return to writing in the “lost years” of 1805-09, and her status as a self-educated and supremely self-conscious writer.

In A Revolution Almost Beyond Expression: Jane Austen’s “Persuasion,” I explore the political, historical, literary, and social contexts of her last published novel. To follow the workings of her mind, I pored over the cancelled chapters of Persuasion, marveling at the drive to perfection that led her to extensive revision. I also suggest that misogynistic reviews of Frances Burney’s The Wanderer, together with Austen’s advice to her niece about marriage, inspired the writing of Persuasion. Then I explore the naval and military contexts of the book, show how Austen critiques issues of rank and gender in Scott, and set up a contrast between the constraints of Bath and the revolutionary storms of Lyme. Persuasion, far from being an “autumnal” work by a dying creator, stresses restoration after the grief and jubilee of Waterloo. Austen was neither unlearned nor uninformed.

Since then, I’ve discovered more about her involvement in the real world, for instance in “Jane Austen and Celebrity Culture: Shakespeare, Dorothy Jordan, and Elizabeth Bennet.” Here I suggest that she modelled Elizabeth Bennet on Mrs. Jordan, celebrated comic actress and mistress of the Duke of Clarence, by whom she had ten children. This possibility sheds new light on Austen’s creativity, her quickness in responding to contemporary celebrities and events, and her courage in criticizing public figures. The online version displays the portraits in glorious color. I can’t keep away from Austen, and have nearly finished my third book on her: “Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen.”

After completing my studies at the University of Otago, New Zealand, I wrote my PhD in London, with a playpen round the typewriter and me as my baby son romped around the room. To check a last-minute footnote, I popped him and his basket under the desk in the famous Reading Room at the British Museum, and nobody noticed. After four years in London and three more in the United States, editing Grandison, I returned to the English Department at Otago to teach. I’ve regularly attended the annual meetings of the Jane Austen Society of North America, contribute talks to the American and Australian societies, presented papers at universities and conferences in the USA, Canada, the UK, Australia, and Japan, published articles in Persuasions and elsewhere, and given dramatized readings of Jane Austen with Terry MacTavish. I thought I would die happy at JASNA 2012, when Cornel West gave a shout-out for my Persuasion book. But first, I want to finish my third book on Jane Austen, “Satire, Celebrity, and Politics in Jane Austen.” Nearly there!